Another U.S. competitor, Argentina, has grown its grain production in part by breaking up its Pampas grasslands

This is the fifth and final installment of our series,“Agriculture’s sustainable future: Feeding more while using less.” Part Four looked at the potential for technological innovations to make a significant impact on U.S. agriculture's environmental footprint. The full series is available here.

U.S. farmers have watched for years as Brazil has become an agricultural powerhouse, grabbing increasing market share in soybeans, cotton, beef and other commodities by converting its vast rainforests and savanna into cropland, with plans to expand even more over the coming decade.

Another U.S. competitor, Argentina, has grown its grain production in part by breaking up its Pampas grasslands, a practice that contributes to greenhouse gas emissions.

Meanwhile, U.S. agriculture groups have been struggling to address demands by policymakers and major multinational corporate customers to cut U.S. farmers’ environmental footprint. Now, those groups are hoping the progress producers are making and the work done to document it will pay off in a competitive advantage for U.S. ag exports in the lucrative European and Asian markets.

One reason it might be a good bet, say experts, is the European Union’s new Green Deal, a sweeping set of proposals that include new metrics for agricultural sustainability. Among other things, the EU document calls for measures to curb the sale of agricultural products “associated with deforestation or forest degradation.”

Marty Matlock, a University of Arkansas scientist who advises sustainability programs for numerous U.S. farm commodities, believes that U.S. farmers should have “a significant competitive advantage” against Brazil and Argentina at least when it comes to selling soybeans, corn and beef into the EU, a market of 440 million consumers.

“We have spent the last 15 years developing and documenting our sustainability initiatives that are multi-stakeholder. validated by external parties, have the oversight of our conservation organizations, and the engagement of our conservation organizations, who are also active in Europe,” he said.

Some of the same farming practices, such as conservation tillage and cover crops, that are being sold to U.S. farmers as ways to improve soil health, reduce runoff and potentially make them eligible for carbon credits could also help compete in foreign markets: Scientists are working to produce data that will assure markets and policymakers that those carbon-conserving practices reduce the environmental footprint of animal feed and the meat and dairy products the feed is used to produce.

For example, the National Cotton Council launched a nationwide initiative in September to set a new standard for sustainably-grown cotton. The U.S. Cotton Trust Protocol “brings quantifiable and verifiable goals and measurement to sustainable cotton production and drives continuous improvement in key sustainability metrics, thereby giving brands and retailers the assurances they need for their supply chain,” says NCC spokeswoman Marjory Walker.

To be sure, the EU rules have raised alarms within the Trump administration because of their potential to discourage the use of genetically engineered crops and pesticides. A recent study by USDA’s Economic Research Service has estimated that the Green Deal strategy will result in lowering Europe’s agricultural production by 12%.

The Green Deal "Farm to Fork" strategy goes so far as to suggest replacing some traditional feed sources, such as "soya grown on deforested land," with alternatives such as insects, algae and fish waste.

The standards that exporters will have to follow to keep selling into the EU market are still a moving target, too. An executive with the European Feed Manufacturers’ Federation told Agri-Pulse in an exclusive interview that U.S. soybean exporters will likely be required to tighten their sustainability standards.

But Jim Sutter, CEO of the U.S. Soybean Export Council, believes that U.S. soybeans should benefit from the global sustainability push simply because it isn’t grown on deforested land. He said, “Our soy has a great track record from an environmental perspective and from a sustainability perspective.”

Brazil accused of backtracking under Bolsonaro

Brazil used its conversion of forest and grasslands to challenge the United States as the globe's biggest producer of soybeans, surpassing the U.S. in both 2017 and 2019. Brazil now has some of the world’s strictest land-use laws on the books, calling for the preservation of about 66% of its land to native vegetation while the country spends hundreds of millions of dollars to promote carbon sequestration, soil restoration and water conservation, but the country is still often viewed an environmental liability.

Brazilian farmers are required by law to leave between 20% and 80% of their land uncultivated, and agribusinesses there have voluntarily agreed not to source commodities from deforested rainforest. The government is working to improve soil conditions on millions of acres of land through public programs like the Low Carbon Emission Agriculture and Recovery of Degraded Pastures plans.

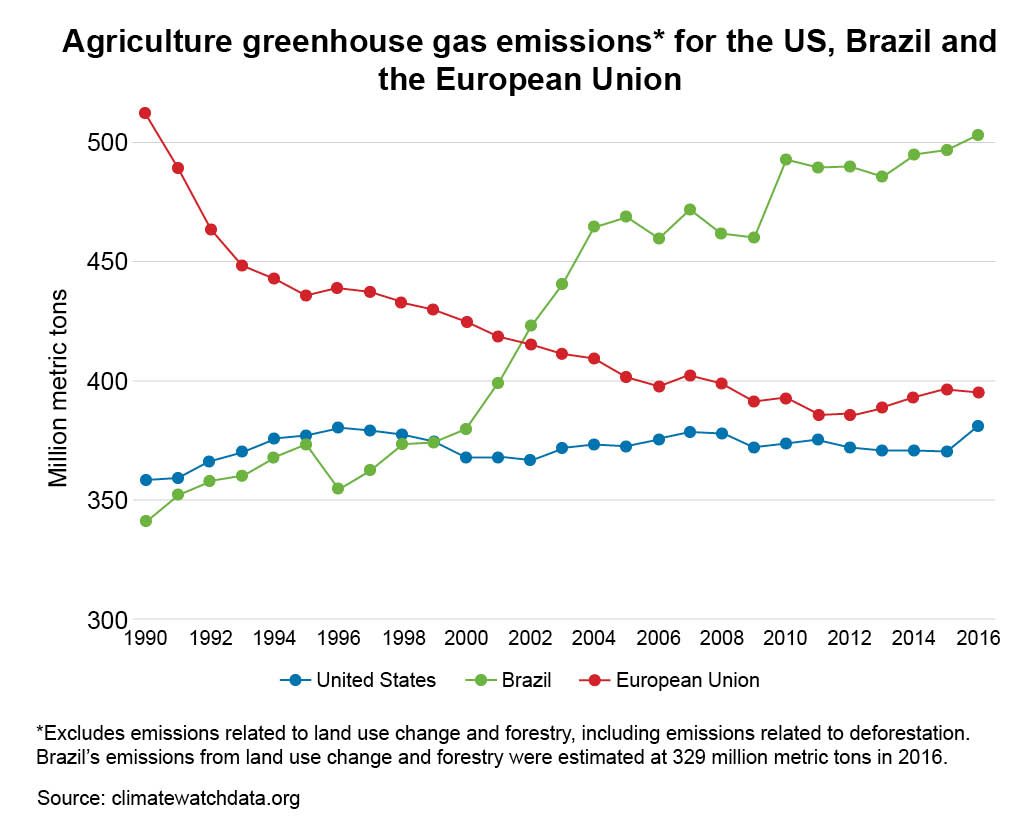

Still, Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions are large and growing. In 2016, the country produced 1.4 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions, including 503 million metric tons from agricultural production alone, according to ClimateWatch, a database managed by the World Resources Institute.

Another 329 million metric tons occurred because of the conversion of grasslands, and destruction of forests.

Argentina had 128 million metric tons emissions from agricultural production in 2016, plus 102 million metric tons from land use change and deforestation.

By comparison, EU and U.S. ag emissions totaled 395 million metric tons and 381 million metric tons respectively, and both the EU and U.S. are net negative when it comes to conversion of grasslands or forests, according to ClimateWatch.

Brazil’s ag emissions are likely to keep growing. Farmers there are expected to increase their plantings of five major crops, soybeans, corn, wheat, dry beans and rice, by 16% over the next decade to 178 million acres, up from 153 million acres last year.

Meanwhile, the Climate Observatory, a Brazilian environmental advocacy group estimates that Brazil’s carbon may have grown by as much as 20% this year from 2018 “depending on the trajectory of the deforestation in the Amazon in the coming months and time for the economy to start recovering,”

Brazil’s environmental reputation took another major hit recently when Vice President Hamilton Mourão unveiled new satellite data that showed the destruction of about 11,000 square kilometers of Amazon rain forest this year – a 9.6% increase from last year.

It’s the highest level of deforestation since 2008, according to data maintained by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation. Mourão tried to downplay the new data, stressing that the rate of increase in deforestation has been higher in recent years, but the negative backlash, domestically and internationally, was immediate.

Carlos Rittl, a senior fellow at the German Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, proclaimed President Jair Bolsonaro’s “great achievement when it comes to the environment has been this tragic destruction of forests, which has turned Brazil into perhaps one of the greatest enemies of the global environment and an international pariah too.”

Not much thought would have been given to the situation twenty years ago. The annual accounting of Amazon deforestation rarely made the front pages of newspapers. But that’s changed as feed and food companies around the world are increasingly concerned about the widening awareness of climate change as consumers increasingly demand their food is sustainably produced.

Brazilian officials argue that much of the country’s increase in crop acreage these days comes from the conversion of cattle grazing land into soybean fields.

“If we only use the pasture that’s underdeveloped and under-used, that would be enough for us to expand our production harmlessly,” one official told Agri-Pulse.

But breaking up grasslands for crops releases carbon into the atmosphere and deforested land is being turned into ag production, even though the process can take years and the government is trying to verify land deeds.

“It is key to continue focusing on landholding regularization,” the official said. “If it is clear who owns the land, authorities can enforce the law more effectively."

While most of the acreage expansion is indeed expected to occur on pasture land that is no longer being used to graze cattle – that’s especially true in Mato Grosso – much of the expansion will also be realized by the “clearing of new land for production” in states like Maranhao, Tocantins, Piaui, and Bahia, according to a recent report by the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service.