Ariel Patton

Over the past several years, there has been an overwhelming emphasis on one little element in agriculture – carbon. More specifically, storing carbon in soils through agricultural practices to combat climate change and provide a host of other benefits.

While carbon sequestration is an exciting starting point, it captures one small slice of how agriculture interacts with the environment – the living, breathing, complex ecosystem made up of land, water, air, billions of organisms and human communities.

For the past 12,000 years since humans started farming, agriculture has been one of the most significant ways that humans shape the environment. In the past 200 years alone, the human population has experienced exponential growth that any start-up would envy, growing from 1 billion people to 8 billion people. To enable this population rocket ship, the demands on agriculture have also had explosive growth.

Beyond simply feeding 8 billion people, we rely on agriculture for other products like fiber, and increasingly, for fuel too.

So what does this look like by the numbers?

-

There are 41 million square miles of land on Earth that aren’t covered by rocks, ice, or sand. Nearly half of those habitable acres are used for agriculture.

-

Globally, 70% of all freshwater is used for agriculture.

-

In the US, agriculture accounts for 10% of the greenhouse gas emissions. Globally, agriculture contributes 26% of emissions.

Using natural resources to take care of humans seems generally like a Good Thing to Do. However, all consumption has a cost. How we work to minimize those costs is where sustainability comes into play.

Cue sustainability in agriculture

Sustainability can be defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

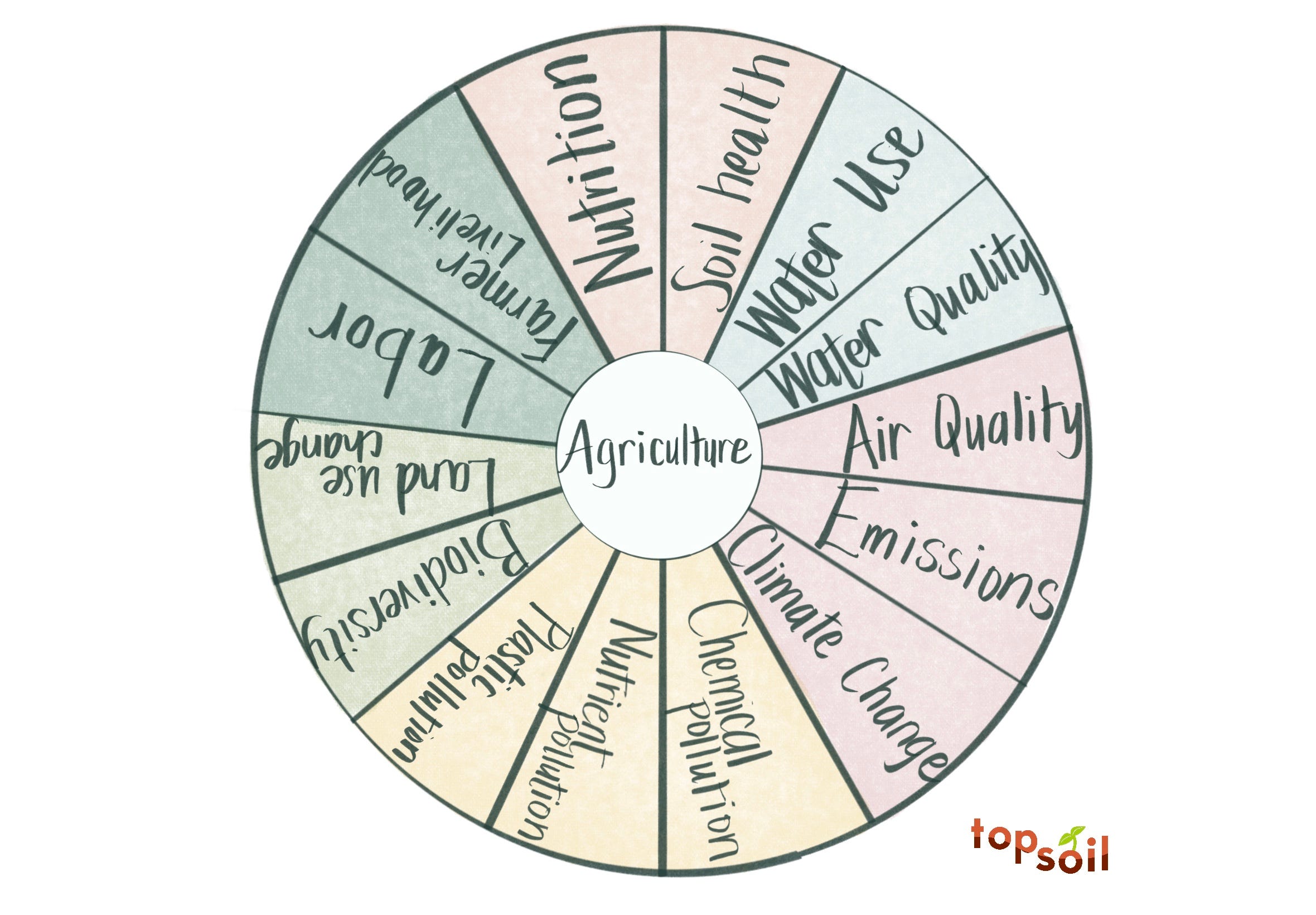

Because of the deep connection between agriculture and the environment, there are many areas beyond carbon where agriculture plays a huge role for a more sustainable future:

|

There are several ways in which agriculture and the environment interact. Let me know in the comments if there are other areas that are missing!

Agriculture being at the center of the wheel above isn’t implying that agriculture is solely responsible for every slice of the pie – more that agriculture can also help to mitigate, adapt to, or even reverse every single one of those challenges.

However, for agriculture to actually produce sustainable outcomes, there must be some actual honest-to-goodness, physical changes that happen on real farms.

The good news is that sustainability isn’t a new concept in agriculture. There is a long-held view of farmers as “stewards of the land” as many have a multi-generational view of their operations.

The challenging part is that farming is a low-margin business with pesky little details like seasonality and weather. For sustainable practices to come to fruition on the farm, there must be operational and agronomic support for farmers and financial incentive to make it feasible.

A farmer I spoke with in Illinois neatly summarized the tension and obstacles to adopt sustainable farming practices more broadly: “The idea of increasing organic matter in the soil for the next generation sounds great. But at every point in time, I am under pressure to be profitable, otherwise there won’t be a farm to pass on to the next generation.”

Also, many of the practices that produce sustainable outcomes aren’t overnight successes. Another Illinois farmer I spoke with had been experimenting with cover cropping and reducing tillage for the past 4 years to increase organic matter in his soil. After 4 years, he hasn’t seen any changes in his soil tests. He admitted, “It’s discouraging, but I am going to stick it out for a few more years because I have heard it can take 7 years to start to see results.” Can you imagine trying anything, say a new workout routine, where you didn’t see results for 7 years?!

Financing sustainability in agriculture

This brings us to a conundrum with agriculture and sustainability – how can more sustainable practices be adopted to address urgent environmental challenges? We know that changes have to take place at the farm. We know that farmers struggle to finance and bear the risk of new practices. Knowing all that, we need to look at financing and risk-sharing across the ag value chain to accelerate adoption.

There are a few ways that this is playing out today.

First, the government has increasingly been investing in sustainable agriculture. The US Federal government allocated $3B last year to launch the Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities, and recently announced another $300M as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, among other investments. There are many other examples at the state level and across the globe.

In other cases, some consumers opt to pay more for sustainably produced products. Whether through paying slightly more for organic produce or regeneratively farmed goods, premiums allow consumers to share some of the costs with farmers.

Investors also fund some sustainable innovation and practices. Since 2020, there has been $23B invested by venture capital into 491 food and agriculture sustainability related companies. Beyond venture capital, there are other funds that focus on sustainable investments.

|

Source: Climate Tech VC newsletter

Corporations are also getting out their checkbooks to finance environmental sustainability in a couple of ways. Carbon marketplaces have sprung up to allow corporations to purchase certificates representing carbon that has been sequestered by farmers to offset the company’s emissions.

While much has been said about the challenges and growing pains of carbon markets, corporations are also making investments directly to meet an increasing number of sustainability commitments. You may have seen some recent eye-popping headlines like PepsiCo and Walmart pledging $120M to accelerate regenerative practices on 2M acres as one example.

Let’s dig into these direct commitments to see how that might accelerate sustainability.

Corporate approaches to environmental sustainability

Reading dozens of sustainability reports from top agriculture companies may sound like a jargon-filled snoozefest to you. It sounded like a nice little Saturday to me.

I wanted to understand a few things. What kinds of promises were being made and why? What opportunities are being created for the rest of the ag value chain? Most importantly, will these promises actually result in more sustainable outcomes, or is it mostly feel-good corpspeak?

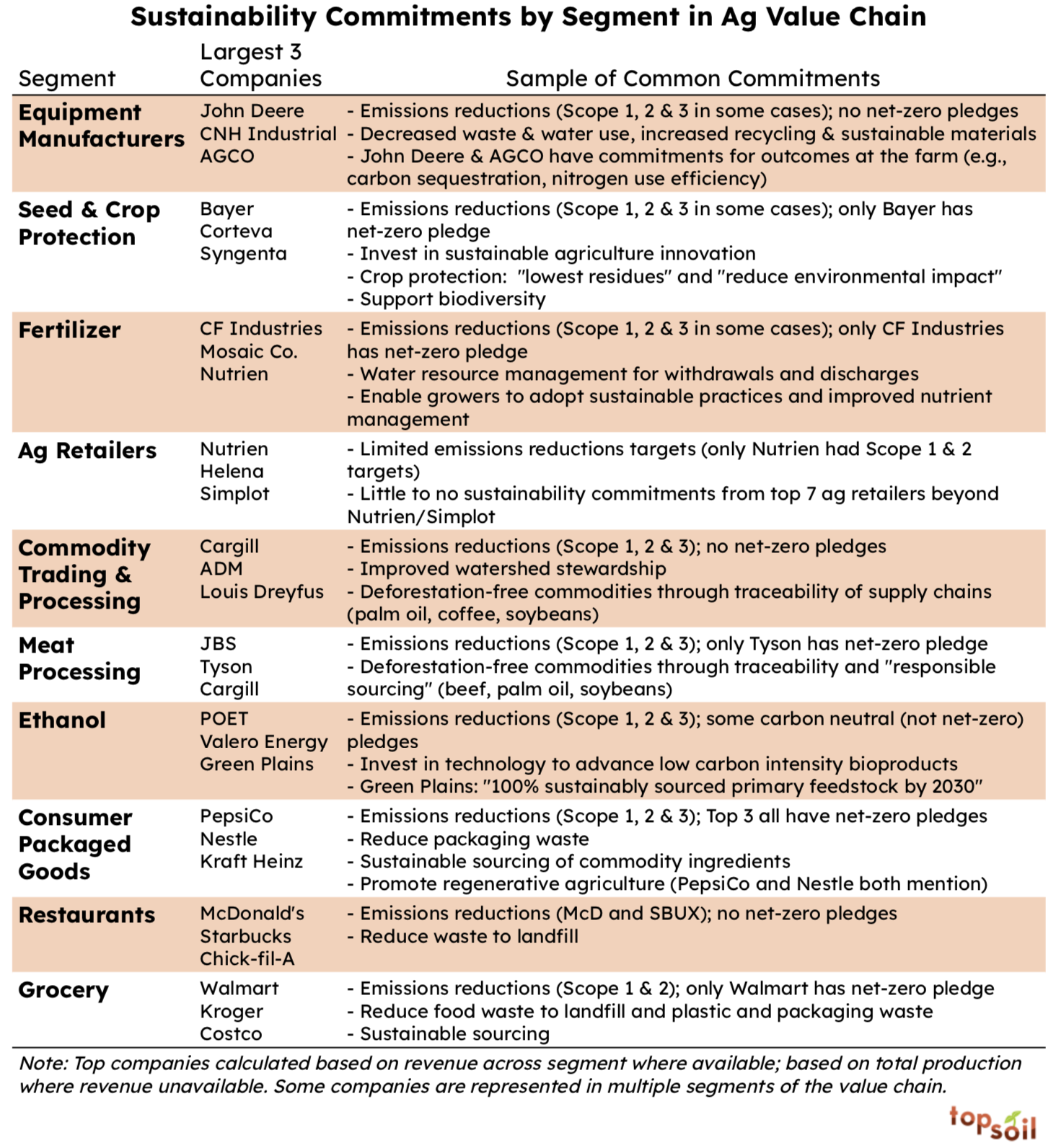

I looked at the sustainability reports for the top 3 companies in each segment of the ag value chain (by US revenue). In total, I analyzed 32 companies and over 270 distinct environmental sustainability commitments (many reports also include commitments around people and community, which I excluded to keep it simple). You can check out the full list here as I’d love to hear any other takeaways you have.

Below is a high-level summary that shows common themes of each segment (a primer on Scope 1, 2 & 3 emissions follows to understand those commitments better):

|

First key takeaway: Sustainability commitments vary depending on what the business does, the company’s stakeholders, and where the company operates.

Goals are, not surprisingly, often tied to each company’s core product lines. For example, many of the equipment manufacturers emphasize sustainable materials used in their equipment and increased efficiency in the manufacturing process. The ethanol processors have many commitments on innovation and lobbying for biofuels.

A company’s stakeholders influence the types of goals set. For example, in the ag retail sector, beyond Nutrien and Simplot (who both have other business lines beyond ag retail), none of the top 7 companies which represent 50% of the ag retail market have any publicly stated sustainability goals.

This could be because the ag retail stakeholders (customers, owners, etc.) do not perceive environmental sustainability as a priority, or ag retail is providing these services without stated commitments, or there simply isn’t incentive for retailers to make sustainability commitments. In any case, this seems like an important missing link in bringing more sustainable farming practices to life at the farm gate. Ag retailers are critical trusted advisors for many farms by providing agronomic support, which is necessary to drive towards sustainable practices.

Companies that do business across the globe, particularly in Europe, tend to have more robust environmental sustainability commitments. This is likely due to differences in regulations across geographies.

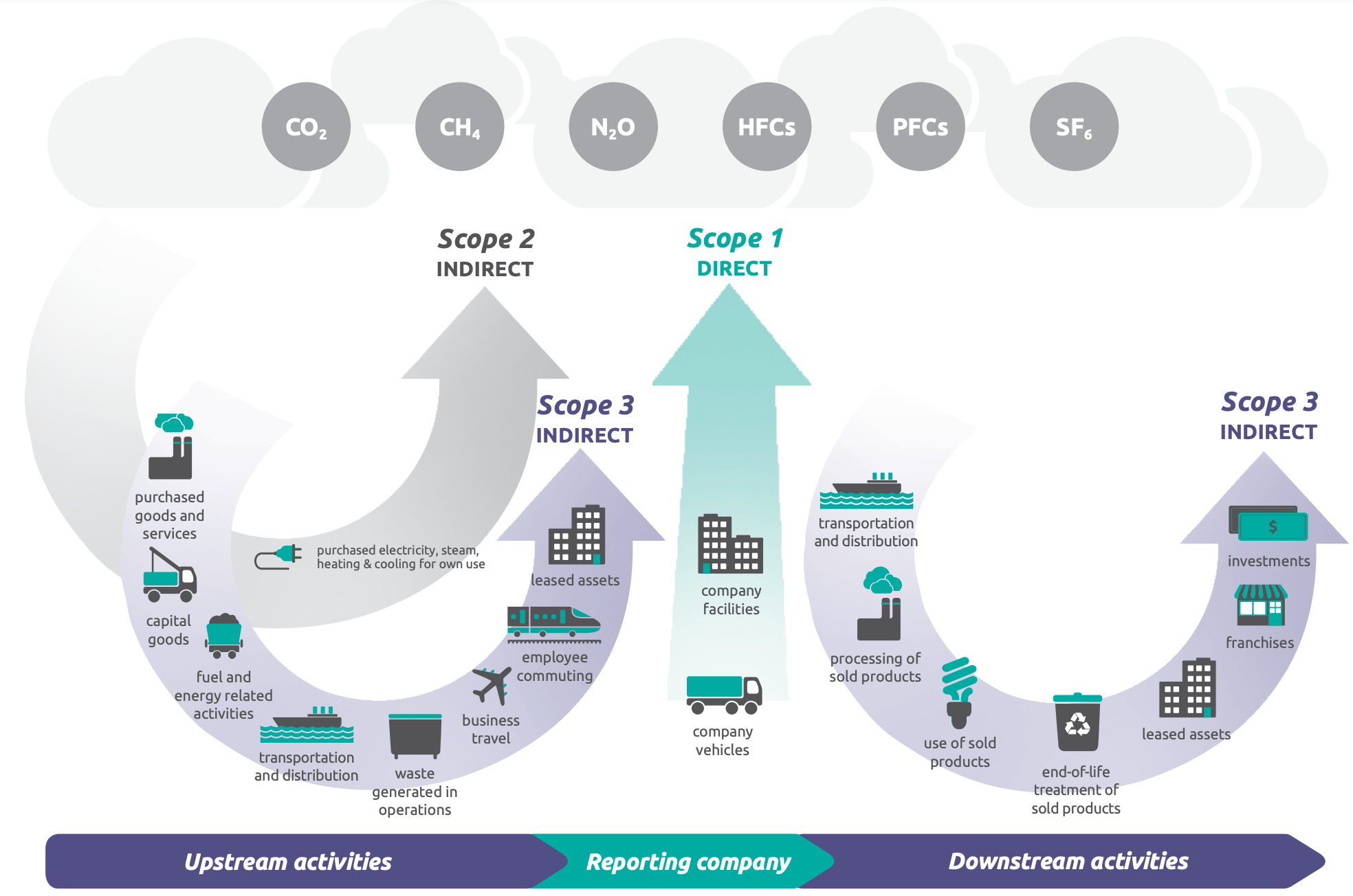

Of course there were some consistent themes across many of the sustainability commitments. Several reference existing international frameworks like the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Limiting carbon emissions is front and center for many companies (with the gold-standard for emissions being the SBTi to reduce emissions to limit global warming by 1.5°C). As a refresher on Scope 1, 2, and 3, the diagram below shows what is included in each category (from the perspective of the company).

|

Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol, Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard

While there is huge variability in companies’ commitments to reduce Scope 3 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, there is another related concept that companies also seem to differ on. Some companies made commitments on only those things that fit within the four walls of their business – they are focusing on what is squarely under their direct control.

Other companies seek to influence beyond the boundaries of the company. For example, John Deere has several goals to “Enhance Ag Customer Outcomes by 2030” by increasing crop protection efficiency, nitrogen use efficiency, and reduce carbon emissions from farming. Similarly, Bayer has a commitment to reduce the GHGs of key agricultural crops. There are a handful of other ambitious goals that will likely be more challenging to execute, but promise to have a much larger impact.

Second key takeaway: the drive towards more environmentally sustainable agriculture will have ripple effects throughout the ag value chain within the next decade.

Many of these commitments are time bound. Unlike that friend who promises that “we should get together…soon!” meaning never, many of these commitments have specific dates, 2030 being a popular deadline. By my best calculations, 2030 is less than seven years away. These deadlines are driving investments and actions today in many cases.

New commitments are coming fast and furious. Over the past year, the number of food and agriculture companies with climate-focused SBTi commitments has nearly tripled. There’s tangible momentum here.

As 2030 approaches, these commitments will require: new investment, new technology, new (and more) talent, new and better connected data, new agronomic research, and new business models to pull all the pieces together.

In short, it’s supply and demand baby! These commitments signal new demand for increased sustainability in agriculture, which will increase the supply of all the above to attempt to meet that demand.

Third key takeaway: Making environmental sustainability commitments is rational, savvy business strategy.

To my cynical friends and Milton Friedman fanboys out there. I see you. Why the heck are corporations even doing this?

Understanding incentives help us understand behaviors. In this case, there are many logical incentives for corporations to take industry-shaking action beyond the lofty language of being a “good corporate citizen.”

We’ve already talked about how sustainability commitments can attract investors.

These commitments can also attract talent. It may sound like the most clichéd statement of all time to say “people look for meaning at work, and Millennials and Gen Z really care about the environment.” But this appears to be true!

After talking with many new faces interested in agriculture, a common theme has been growing over the years – agriculture is a compelling industry to work in because it can combat climate change and drive environmental sustainability forward. Several studies, like this one, find that 37% of Gen Z and 33% of Millennials report that "addressing climate change is my top personal concern". Increasingly, sustainability will become a top reason that new employees are attracted to agriculture.

Sustainability commitments may increase credibility for companies with products that have sustainability marketing claims. Bayer, a company leaning into products with a regenerative agriculture angle, said this most directly in their recent sustainability report: “This leads to new business opportunities for ourselves that benefit the environment at the same time.”

Many of the companies I looked at have been around for nearly 100 years. That kind of longevity requires careful risk management. As we sit here in 2023, there are many kinds of risks that are being managed with sustainability commitments.

For one, particularly for companies that rely on sourcing agricultural goods for their supply chains, climate change and extreme weather events put pressure on supply of key inputs. Through these commitments, corporations, particularly further downstream like CPG, can ensure a more resilient supply chain and reduce this sourcing risk.

Second, there is reputational risk by ignoring environmental challenges. In a Pew Research Center study, 69% of US adults say corporations are doing too little to reduce the effects of climate change. By voluntarily curbing emissions and making sustainability commitments, businesses can often preempt regulation. Businesses can earnestly throw up their hands and ask: why do we need regulation when we are already solving the problem without government intervention?

I share the above not to cheapen the commitments being made, but to make it clear that these commitments are here to stay – as long as the incentives of more talent, investment, differentiation, and risk management remain in place.

Final takeaway: These promises are a good first step, but more work needs to be done to ensure they actually result in more sustainable outcomes

I couldn’t get through an edition on environmental sustainability without mentioning the dreaded “g” word. Greenwashing. Greenwashing happens when companies misrepresent their environmental record – painting a rosier picture than reality. Sometimes this is intentional, sometimes this happens through good intentions and poor execution.

Beyond greenwashing, there are valid concerns that companies: 1) won’t actually meet their commitments even when trying their darndest, or 2) won’t actually create positive outcomes for the environment even if commitments are met.

To me, accountability to protect against these outcomes is in need of investment, innovation, and rigor. MRV (measurement, reporting, verification) is often talked about in carbon emissions accounting, however the general concept can and should apply to many other measurable commitments – whether targets around biodiversity, ingredient sourcing, or freshwater consumption. While there is a rapidly evolving set of tools, practices, standards, and oversight to drive accountability, more is needed. And of course, in any of the commitments listed above, the devil is in the details of how the commitments are defined, such as “sustainably sourced” or “low carbon intensity.”

Measuring sustainability outcomes can be challenging. In many cases it’s easier to measure inputs instead of outcomes. For example, in many carbon markets, to generate a credit, farmers are paid on their practices (e.g., no-till or cover cropping) instead of on actual measurements of organic matter increasing in the soil. Many outcomes cannot be measured at scale, or require massive amounts of data to be collected, which is not always feasible.

Since agriculture is massively complex and interacts with the environment in many ways, it can also be difficult to quantify tradeoffs. Is it better to avoid spraying synthetic herbicides, but instead increase tillage to manage weeds (or, in some cases, burn propane to eradicate weeds with fire)? This is one tradeoff among many which do not have clear answers.

Beyond MRV, it is also unclear who will hold companies accountable if they miss their targets. In some cases it may be activist investors, or concerned employees, or disgruntled customers. In many jurisdictions, government enforcement for greenwashing is nonexistent. Enforcement mechanisms are likely to evolve over time, but in 2023, it’s still murky.

Corporations are only one piece of the puzzle. For species-level challenges like climate change, it’s going to take much more than just corporate action. As exciting as it is to see the increasing momentum, it is estimated that we still need 7x the current levels of investment to mitigate and adapt to climate change. In an industry as consolidated as agriculture, corporations providing funding are one necessary lever for agriculture to be, as cheesy as it sounds, part of the solution.

Ακολουθήστε το Agrocapital.gr στο Google News και μάθετε πρώτοι τις ειδήσεις